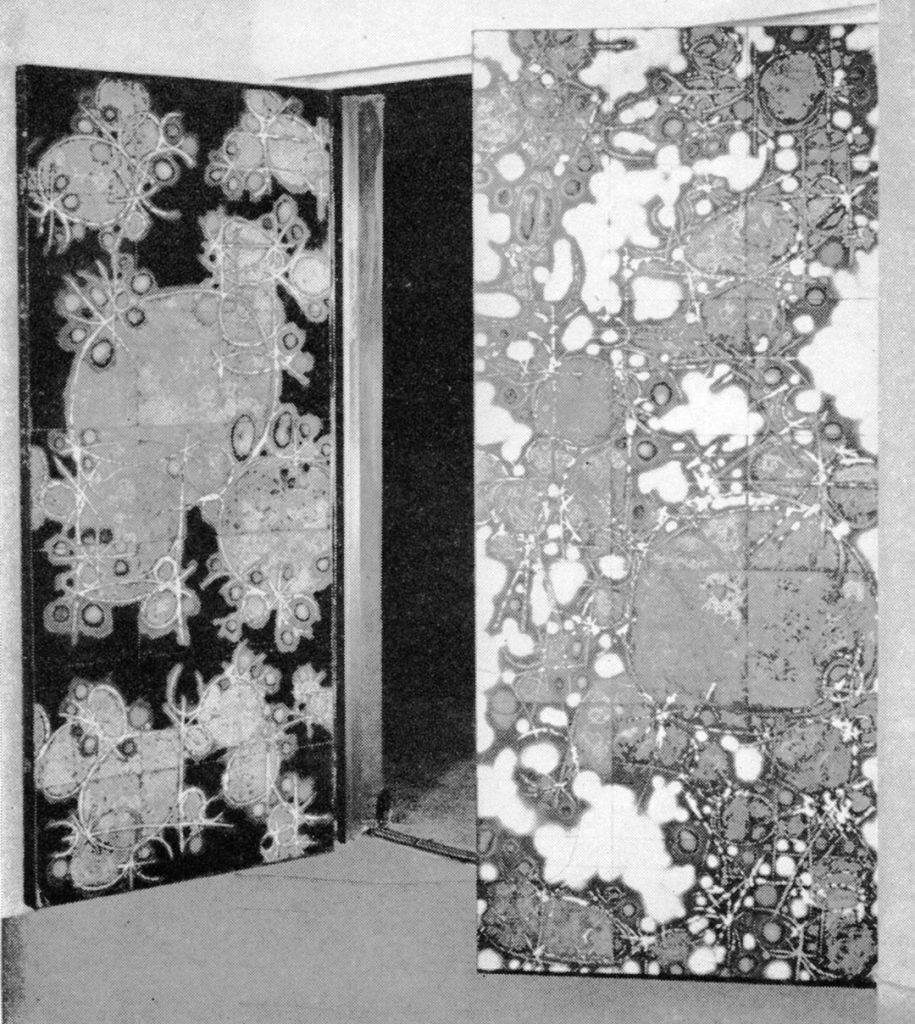

Doors, each 3′ x 7′, of painted enamel on oxidized copper at Living Theater in New York City have reds, oranges and blues with white on interior face and with black on exterior.

Paul Hultberg’s murals exemplify what has happened to enamels in the 20th century. They have gotten big. They can be used architecturally.

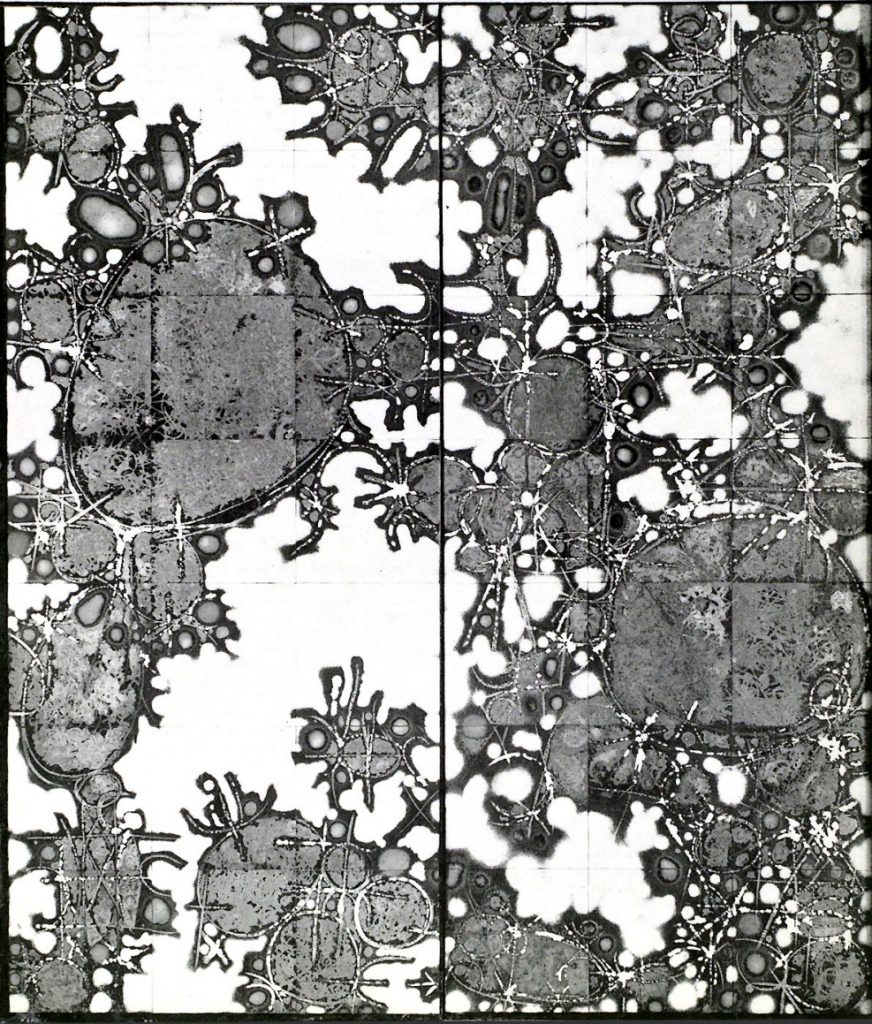

An enameled copper screen, six by eight feet in size, designed and executed by Hultberg, greeted each visitor as he entered the fall show of contemporary enameling in the U.S. at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (N.Y.C.), September 18-November 29. Other of his wall panels in the exhibition—tall and narrow, square, horizontal—represented Hultberg’s approach to the visual, spatial art. Characterized not only by size, his work at present is also distinguished by his emphasis upon the brush stroke as means of application of the enamel and upon oxidation patterns. His palette usually moves among whites, blacks, rusts. Recently, Hultberg has been developing a new paste enamel in which clay has been mixed and with which he painted directly upon the copper sheet. This new formula creates an image that suggest ceramic tone and an impasto paint surface. He has made a scale model of a free standing hollow wall, six feet tall and twelve feet long, completely faced on all sides and ends with a mural of this type.

“My interest has always been in murals,” he states, “I had a mural business in California years 11 years ago, working with plastics. I had learned the techniques in the workshop with Jose Gutierrez in Mexico City. Although the first murals we did there were frescoes, Jose Gutierrez was more interested in the new media that would withstand outdoor exposure and combine imaginatively with modern architecture. He introduced me to vinyl acetate resins, cellulose nitrate resins and silicon-ester (used to preserve stone by developing on its surface a deposit of pure silicon, constituting a type of ceramics without heat).

Doors, each 3′ x 7′, of painted enamel on oxidized copper at Living Theater in New York City have reds, oranges and blues with white on interior face and with black on exterior.

“Enameled copper murals have great possibilities. They can be made weather resistant by careful mounting. Also, the color range is as inclusive as painting or glass. As shiny enamels tend to reflect light and produce glare, I myself like matt surfaces. The matt effect of naked copper, when treated with oxidation patterns, can have the quality of sculpture: the copper is the form, and the enamel delineates that form.

“One of the technical problems in enamels is warpage. I use a light 28 gauge copper because it is easier to get the warp out. Most enamelists, I understand, use an 18 or 20 gauge. Peterson, the Norwegian enamelist, did research in Europe and told me that many early enamels had been done in light gauge metal. I was glad to hear I had precedents!

“My approach to enamels was originally as a printmaker. While teaching painting, drawing and design at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, I had the opportunity to do experiments in enameling for a year. Walter Rogalski, also a print maker and engraver, joined me in this work. We took off from our point of view of our interests in painting and print making and fooled around in the medium not in the traditional way, but in ways that suited us.

“For one thing, the print maker has a taste for indirect effects, not like the painter, who makes a stroke and there it is—paint. In print making, it is a matter of doing something that does something else: scratching the plate, wax resist, acid, , all kinds of texturing and multiple printings. In enamels, also, the tecniques are indirect. You have the enamel as a granular, sand-like pigment. The problem is how to get this where you want it. It doesn’t handle like paint. The firing changes its coloring and texture. As in print making or ceramics, you don’t know exactly how it will come out.

• 9″ x 27″ panel with white, black, red and silver enamels painted on oxidized copper.

“Another thing that attracted me to enameling was that it forced me to complete something. In painting, when are you finished? In enameling you are finished when the technical requirements have been fulfilled.” This statement, of course, was belied by the pile of “failures” in a corner of Hultberg’s studio, which were technically completed but had not satisfied the enamelist imaginatively.

After the Brooklyn Museum, Hultberg shared a studio with potter Hui Ka Kwong and then did commercial enamels for three years, making more, he estimates, than 45,000 pieces. In 1965, he and his wife and two children (now four) moved to Rockland County as members of the Gate Hill Cooperative near Stony Point, New York where craftsmen David Weinrib, Karen Karnes and M. C. Richards were living and working.

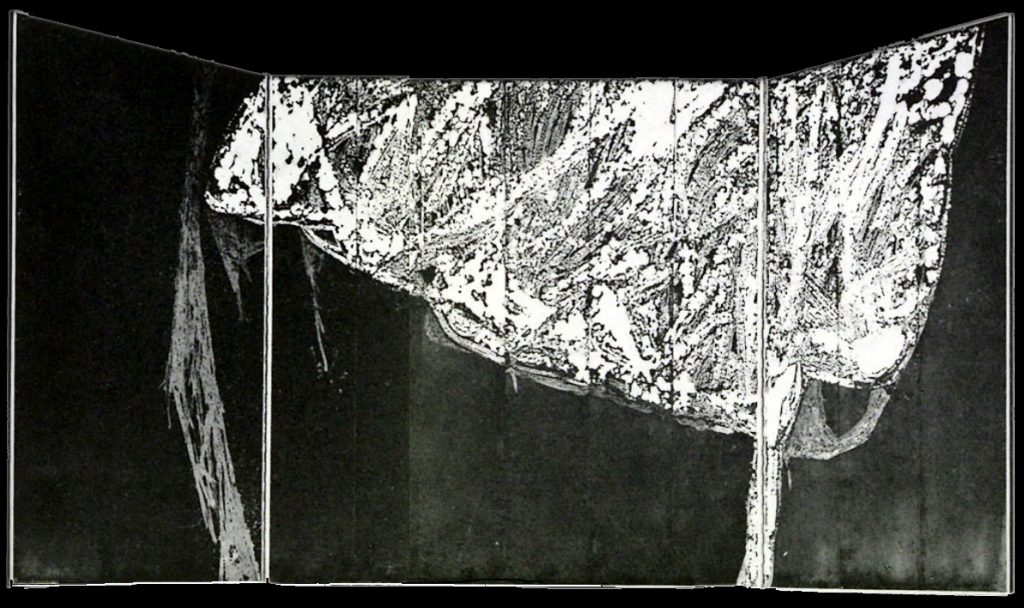

Painted enamel on copper triptych, 3′ x 6′ has white and black enamels combined with copper oxides.

His studio at Gate Hill in the lower floor of his house, which was designed by Coop architect Paul Williams. He has two kilns, a long firing bed of his own design for large panels under which rolls a cart holding gas torches, two large work tables and mural show space. Williams commissioned an enamel mural for the outside wall of his woodshop nearby, which Hultberg completed three years ago.

For the past three years Hultberg has concentrated upon enamels for walls, screens and panels–with the encouragement and cooperation of Jack Lenore Larson, Karl Mann Associates and the Martha Jackson Gallery, all in New York City.

Born January 6, 1926, in Oakland, California, one of three blonde brothers (a sister, also blonde, came last(. Paul Hultberg was the one known in adolescence as the “artist”. Brother John Hultberg the painter, was then the “writer”; brother Donald, now a physicist in California, was considered the “musical one.” There mother died during their childhood, and their lives revolved around first one relative, and then another, from the Bay Area to Los Angeles. “My father was interested in the common man, in the solution of social and economics problems. My mother was interested in the uncommon man. Sometime I think I have inherited in myself the argument between them. I have the practical interests of my father, plus a tendency toward self effacement; at the same time I have always had a strong feeling of personal destiny.”

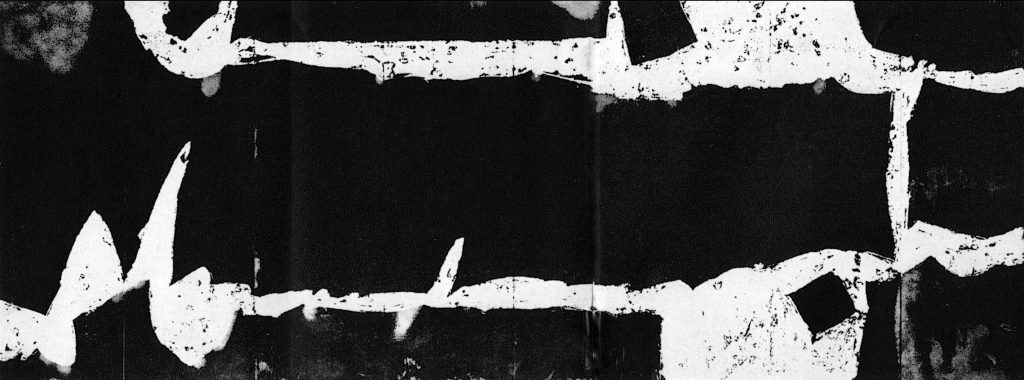

Panel, 3′ x 8′, of painted white enamel on oxidized copper

Hultberg is almost as close to inventor as to artist. He has, for example, created a mural process called “Photojector,” which combines the techniques of photography and painting and enables an artist to affix a projected image upon a surface..

He works from “an intention of the size and how I am going to break it up. And as the copper I use comes in widths up to 14 inches, this is an important element in my work. It is part of the craft of mural making to be adaptable to shape. The long thin shape and the square shape particularly interest me, partly because of the difficulties they present.”

He starts by making a number of drawings, feeling out the forms. Then he does color samples, handling the forms to color on scale model enamel panels. He works with one or two firings, and at most three. By applying all elements of his designs for the first firing, the second one may involve only an over-all color or clear glaze.

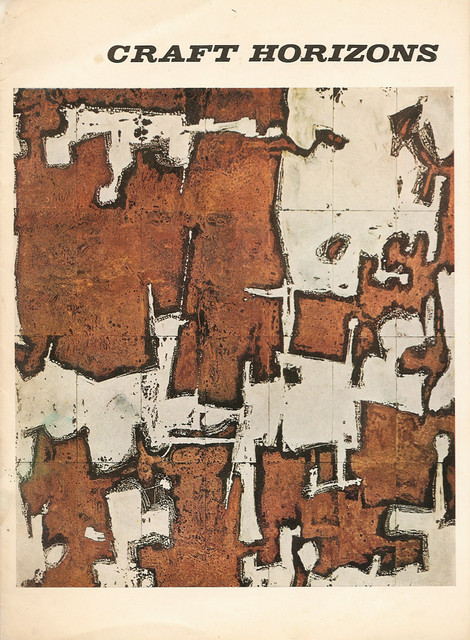

This was the Fall cover for the 1959 Crafts Horizons magazine that featured the work of enamelist Paul Hultberg. The M.C. Richards’ article came out in the following Spring edition in 1960.

The following steps constitute Hultberg’s usual procedure:

1/ Cuts a piece of copper with a paper cutter, rolls it flat, cleans it with steel wool.

2/ Brushes on design with glycerin and water, which tends to roll and skip on the somewhat oily metal surface; brushes this with mixture to which a commercial binder, “Klyr-Fyre” has been added, somewhat dissolving the oil. These two steps underlie the application of the enamel, which is shaken through a tea strainer over the panel and then dusted off. The enamel sticks to the brush strokes, furthering shaping with brush end.

3/ Bare areas are sometimes brushed with a mixture of vinegar and salt, which influences the oxidation occurring during the firing. The brush work here also retains the character of the stroke–pressure, length, speed, area–a sense of kinetic forces pressing outward.

4/ Lays panel on metal rods of firing bed. Lights torches, passes flames under panel producing red heat, moving flames back and forth to melt the enamel dust. Thereby producing oxidation patterns on bare metal.

5/ Removes panel from bed, rolls it flat as black oxidation pops off and is brushed away, leaving marbled image in blacks, reds and rusts, vivacity of metal on which thick white glass floats.

6/ Applies wax, which slightly darkens the panel. Often with age and exposure, the naked copper may further darken and become green like bronze, an effect which Hultberg likes.

Hultberg’s enamels are distinguished by their use of the copper itself and by their size. “Michelangelo was the earliest influence upon me,” he says, “and Korin screens the latest!”

This is the actual cover of the March / April, 1960 issue of Craft Horizons where the Richards’ article about Paul Hultberg was published.

Although his designs tend to be organic, they are not necessarily representational. Outside murals for the new medical offices of Dr. N. Czukor on Route 9W in West Haverstraw, New York, are in bright floral patterns, since the doctor asked specifically for something “cheerful.” Other look like cosmic kites held held to the sea with long craggy tails; ovum forms, scratched, intersected, veined, like highway blueprints. Relief elements are sometimes welded on a vertical surface, and many of the murals give a feeling of being done with pen rather than brush, of having made use of scragfitto through a second application of color.

Installations of Hultberg’s architectural enamels may be viewed at the following locations: Merck International, Church Street, New York City; executive offices, Dorr-Oliver Corporation, Stanford, Connecticut; office doors, Martha Jackson Gallery, New York City; Lobby Doors, Living Theater, New York City; Malvern Jewish Center, Long Island, New York; fireplace hearth, Edina Country Club, Edina Minnesota; exterior paneling, Walden School, Berkeley, California.

Hultberg’s enamels are not the little jewel-like miniatures one sometimes associates with this craft. His surfaces are the more original expressions of an artist who mixes the visions of painter, print maker and adventurous inventor.

——————————–

This article on PAUL HULTBERG by M. C. Richards was first published in the March / April 1960 issue of CRAFT HORIZONS magazine.