Enameling In the Footsteps of Painting: Karl Drerup and Paul Hultberg

Makers: A History of American Studio Craft, Chapter 7 1950–1959 The Second Revival of Crafts

By Janet Koplos and Bruce Metcalf

By the mid 1950s enameling had become a popular pastime. Many of the jewelry-making textbooks published in the 1950s devoted a few pages to it, and Kenneth Bates’s comprehensive Enameling: Principles and Practice first appeared in 1951. A more accurate sign of the times may have been the 1953 publication of Enameling for Fun and Profit. Enamel in jewelry proliferated. Typically a cloisonné would be mounted in a bezel setting, somewhat like a large flat stone, or small panels would be linked together to make bracelets. This introduction of color to jewelry was seductive, and many people tried their hands at it. Results were mixed. Many jewelers failed to protect the edges of the enamel, leaving it prone to chipping, which gave the medium a bad reputation.

Teachers and professionals in the enameling field had to distinguish their work from the volumes of hobby work. They could do so by complete mastery of technique, larger scale, or artistic sophistication. Bates, with his encyclopedic knowledge of enameling, chose the first option. Monumentality was a path explored by Edward Winter in Cleveland, who created decorative architectural panels using the medium. The third approach for enamelists was following painting, which presented a moving target. What seemed adventurous at the beginning of the 1950s was passé by the end of the decade, and artists who did not change accordingly fell out of fashion. The trajectory can be clearly traced in the differences between Karl Drerup (1904–2000) and Paul Hultberg (born 1926).

Teachers and professionals in the enameling field had to distinguish their work from the volumes of hobby work. They could do so by complete mastery of technique, larger scale, or artistic sophistication. Bates, with his encyclopedic knowledge of enameling, chose the first option. Monumentality was a path explored by Edward Winter in Cleveland, who created decorative architectural panels using the medium. The third approach for enamelists was following painting, which presented a moving target. What seemed adventurous at the beginning of the 1950s was passé by the end of the decade, and artists who did not change accordingly fell out of fashion. The trajectory can be clearly traced in the differences between Karl Drerup (1904–2000) and Paul Hultberg (born 1926).

Drerup trained as a painter and printmaker in his native Germany. Even as a youth, he was conservative, studying etching and figure drawing while his friends participated in the artistic foment of the Bauhaus. As fascism overtook Europe, he and his wife fled to the Canary Islands and then to the United States, in 1937.

Drerup’s first exposure to contemporary enameling was at a New York showing of a Ceramic National exhibition, where he saw an Edward Winter piece. (Because of the technical similarity between enameling and glazing, ceramics and enamels had been lumped together since the Arts and Crafts period.) Hearing that enamels could be produced more quickly and less expensively than ceramics, Drerup set about teaching himself. He read all the books he could find and experimented. By 1940 he was earning a living making enameled trays, plaques, and jewelry, but his primary ambition was to treat enameling as a form of painting.

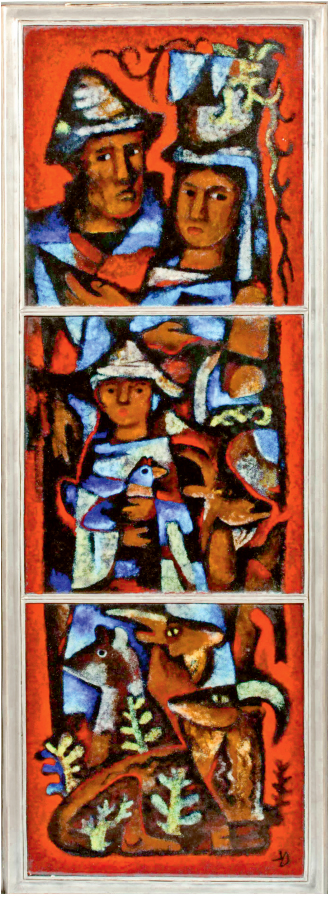

A love of tradition led Drerup to the Limoges technique, in which opaque and transparent enamels are layered gradually over a colored (or bare metal) ground. This technique was ideal for both figuration and lush color effects. He worked in the style of the school of Paris, the avant-garde of his youth. Such paintings featured highkey colors, fractured representation of space, and such conventions as still lifes, harlequins, and female nudes. Many enamelists adopted the style. One of Drerup’s painterly enamels is Three Figures (ca. 1955). (Figure 7.25) The faceting of analytic cubism, saturated colors of fauvism, chunky figures of Fernand Léger, heavy black outlines of Georges Rouault—all derived from painting before 1920—can be recognized in the work. The composition is safe, with the three figures carefully balanced.

For years, Drerup was regarded as the artistic equal of Kenneth Bates. He exhibited widely in enameling surveys, national craft shows, and even the 1958 world’s fair in Brussels. By that time, though, critics were questioning craft’s continuing reliance on outdated art styles. Greta Daniel, a curator from MoMA, was not impressed with a 1959 show of French tapestries that similarly worked with the conventions of the 1920s. She dismissed it with the observation that “‘Styled’ eclectic repetitions of old traditional themes survive there, meaninglessly but enduringly, and with a self-conscious determination which no longer relates to life.”72 Within ten years, Drerup’s enamels lost favor. It is not that his work no longer related to life but that it no longer related to contemporary art.

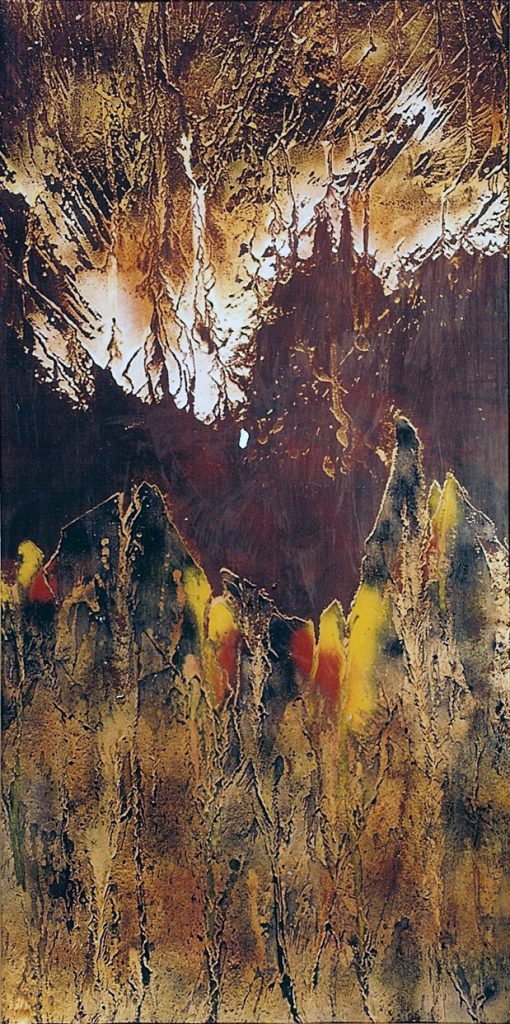

In 1970 the biggest event in the craft field was the Objects: usa exhibition, and Drerup was not invited. Paul Hultberg was. He represented a new generation of enamelists who embraced abstract expressionism. (Figure 7.26) His enamels were big, and he specialized in making enamel look like it was applied in bold brushstrokes. The similarity to paintings by the most graphic of the abstract expressionist artists, like Clyfford Still, was unmistakable. The flavor of urban grit and downtown cool was unmistakable, too.

Figure 7.26. Paul Hultberg, Little Fault, 1972. Enamel on copper; 48 × 24 in. (Courtesy of Lawrence Hultberg. © Paul Hultberg.)

As a young man Hultberg had studied with muralist José Gutierrez in Mexico City. Gutierrez pioneered the use of new synthetic paints to increase the longevity of his murals, and Hultberg became fascinated with the possibility of durable two-dimensional mediums. In the early 1950s, while teaching at the Brooklyn Museum School, he and a printmaker friend started fooling around with enamels, which are durable but cannot be applied like paint (most have a heavy, sandy texture that prevents them from flowing onto a surface).

Hultberg found that he could paint a mixture of water, glycerin, and a commercial binder onto a sheet of copper. Since the mix was thin, it could have all the qualities of an expressive brushstroke. Since it dried slowly, he could sift dry enamel onto the liquid, and the powder would stick. He would then work on the remaining bare metal with another mixture of vinegar and salt, which would etch and encrust the metal during firing. After running through a moving furnace of Hultberg’s design, the copper had splashy brushstrokes in enamel, complemented by oxidized copper in shades of black, rust, and maroon. Hultberg preferred to fire his panels very few times, maintaining a sense of immediacy and bodily gesture. The potter-poet M. C. Richards wrote a glowing article on Hultberg for Craft Horizons in 1959. She noted that his panels were emphatically not jewel-like miniatures, and she enthused about the kinetic quality of his brushwork. Hultberg contributed a fresh new approach to the enamel medium, but he was more of a popularizer than a pioneer. Even as one of his panels was acquired by MoMA for its permanent collection, his enamels were commissioned for apartment buildings, executive suites, doctors’ offices, and the Pan-Am Building. Such wide acceptance suggests that his version of abstract expressionism was, like Drerup’s version of the School of Paris, comfortable. He, too, would be eclipsed by a new taste for decorative, jewel-like qualities. The time for expressionist enamels had passed, and by 1980 his work was seldom exhibited.

Painting like enamel faded after the 1950s. Perhaps the marketplace had been saturated with too many enameled bowls with trite designs, or maybe the medium became inextricably tied in the public imagination to Trinkit kilns and summer camps. There were a few exceptions, such as Bill Helwig (born 1938), a specialist in grisaille (black-on-white) figurative imagery, and Ellamarie (1913– 1976) and Jackson Woolley (1910–1992), who continued to create large architectural work in the School of Paris style. But enameling withdrew to a more intimate scale, to jewelry and vessels in particular. In those two contexts it no longer had to be compared with painting and could find its own standing as a decorative art. Enameling was thus positioned for a renaissance in the 1980s.

——————————————

From the 2010 book, Makers: A History of American Studio Craft, by Janet Koplos & Bruce Metcalf; Chapter 7 • 1950–1959 The Second Revival of Crafts